Shami, Bumrah and Siraj: How do they stack up to the best bowling groups of all time?

India seem set to win another World Cup, with the force of 1.4 billion fans behind them, home conditions, mesmerising batters, and a spin bowling arsenal that’s the envy of the world. Despite all of that, it’s the pace bowling trio that is leading the way, deciding contests almost before they start. But just how good are they?

India’s pace battery consists of Mohammed Shami, Mohammed Siraj and Jasprit Bumrah. All three are different, offering skills unique from the others.

Shami has only played in four games in the World Cup so far and sits fourth in the wicket-taking table with 16 with an average of seven. Bumrah isn’t far behind with 15 wickets of his own and an economy rate of under four. Siraj is arguably the weakest of the three and still has 10 wickets so far.

Shami is a proponent of swing with the new ball and despite not possessing top-end speed, he rushes batters with balls that skid on. He tests batters almost every ball and so rarely bowls a freebie.

Bumrah is probably the best all-round seam bowler in the world, consistently topping 90mph and able to swing it both ways with his unique action and wrist position. The only bowler guaranteed a place in a World XI in all three formats.

Siraj can also swing the new ball, but his ability to ride waves of confidence is unmatched. When he and India are on top, the crowd seems to lift him to new heights. See the Asia Cup Final for evidence.

India are one of the few teams in the World Cup that seems equally comfortable setting a target and chasing. This is due to their perfect balance between seam, spin, and batting. If any one of those falters, the others are good enough to carry the load.

For a fair comparison to the Indian pace trio, we need to look further than the current crop of competition. Australia’s trio of Starc, Hazlewood, and Cummins is world-class, but are far better in red ball than white. With that being said, let’s see how Shami, Bumrah, and Siraj stack up against some of the best attacks in history.

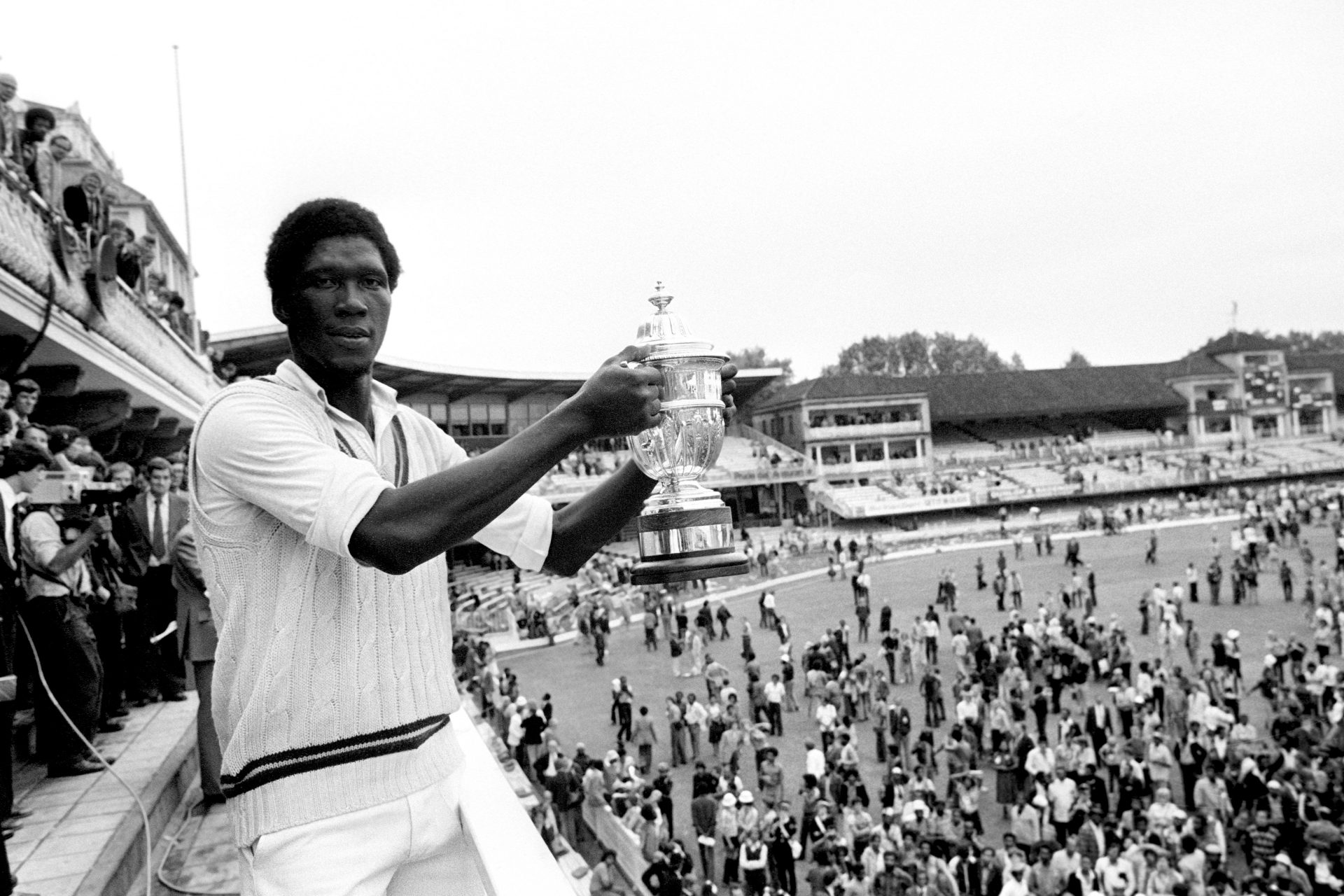

Back in the days of West Indian dominance, there were few more intimidating experiences than facing a pace battery featuring Garner, Roberts, and Holding. Each capable of bowling 90mph+, they tore through England in the 1979 World Cup Final, with Garner taking 11/38.

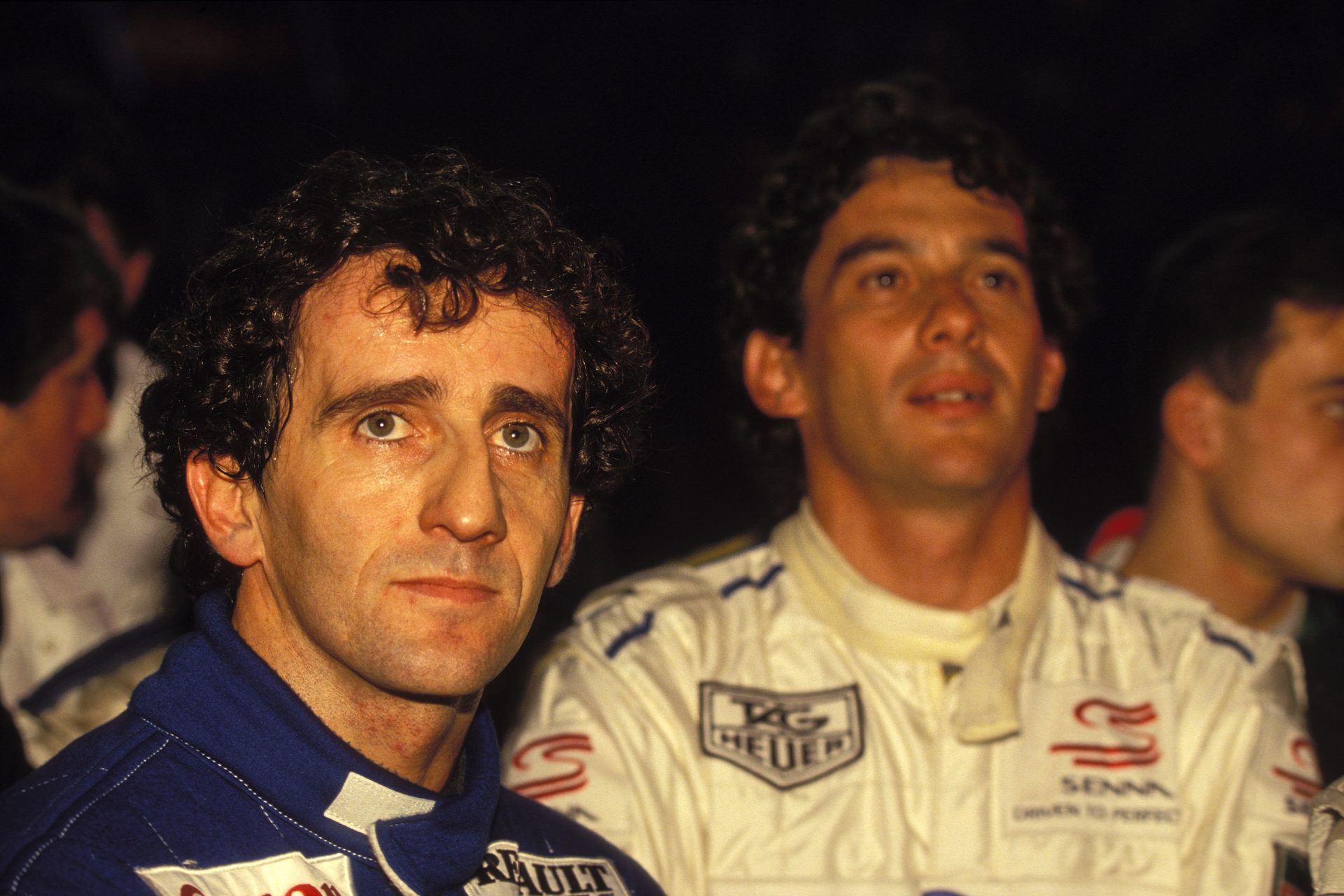

Headlined by Wasim Akram and Imran Khan, Aaqib Javed is often forgotten member of the 1992 Pakistani side. All three were masters of reverse swing with the old ball and made for a formidable matchup for any batting lineup.

Glenn McGrath needs no introduction, but it was the support he received from Damien Fleming and Paul Reiffel that made this pace trio so formidable. It helps to have the wiley Tom Moody and Shane Warne as support options. A large part of the Aussie’s success in 1999 was their miserly pace bowling, giving opposing batters almost nothing.

By 2007, Glenn McGrath was past the peak of his powers but was still formidable at times. Nathan Bracken was ahead of his time, bowling a variety of cutters and slower balls with the ability to swing the new ball. Shaun Tait is arguably the fastest bowler of all time, hitting 95mph+ consistently.

2015-era Mitchell Starc was one of the most dominant ODI bowlers of all time, taking 22 wickets at 10.18 in just eight matches. He was supported by the express pace of Mitchell Johnson and the unerring accuracy of Josh Hazlewood. A perfectly balanced attack.

England’s 2019 World Cup win had explosive batting as its foundation, but in a low-scoring final on a turgid Lord’s pitch, it was bowling that set up the win. Archer’s pace, Woakes’ nibble, and Plunkett’s ability to consistently get wickets in the middle overs made for an incredible trio and that’s without mentioning Mark Wood, Adil Rashid, and Ben Stokes.

It’s difficult to anoint this Indian trio as the best trio of all time before the completion of the World Cup, but if they continue their current dominance, they will have as good a claim as anyone.

It is so difficult to compare across eras given how differently cricket is played in 2023 to 1979. Despite that, it’s tough to look past the great West Indian attack from 1979… for now!

More for you

Top Stories