Why Singaporean children are the best at math

The PISA Report (Programme for International Student Assessment) is the most important educational test in the world. It has been held every three years since 2000. In December 2023, the results of the eighth edition were released.

The results have been a blow at a global level. The countries of the European Union have dropped 14 points in reading compared to the last published report, 6 in science and, significantly, in mathematics, where they dropped 20 points on average.

The report reflects especially high decreases in the mathematics test in most European countries (Norway, 33 points less compared to the last report, or Iceland, 36 points less) but the US also drops 13 points and Chile, the first classified in Latin America, 6.

In this eighth edition (held in 2022), 690,000 students from 81 countries aged 15 to 16 participated, and the general drop can be understood by COVID-19, which affected the educational system for three years. But why is it even worse in mathematics?

Mathematics is the subject that most requires the support of a teacher and is the most difficult to learn alone or with the help of the family. Therefore, the Covid context was not ideal.

However, a dozen countries, almost all of them Asian, have managed, despite the situation, to improve their results.

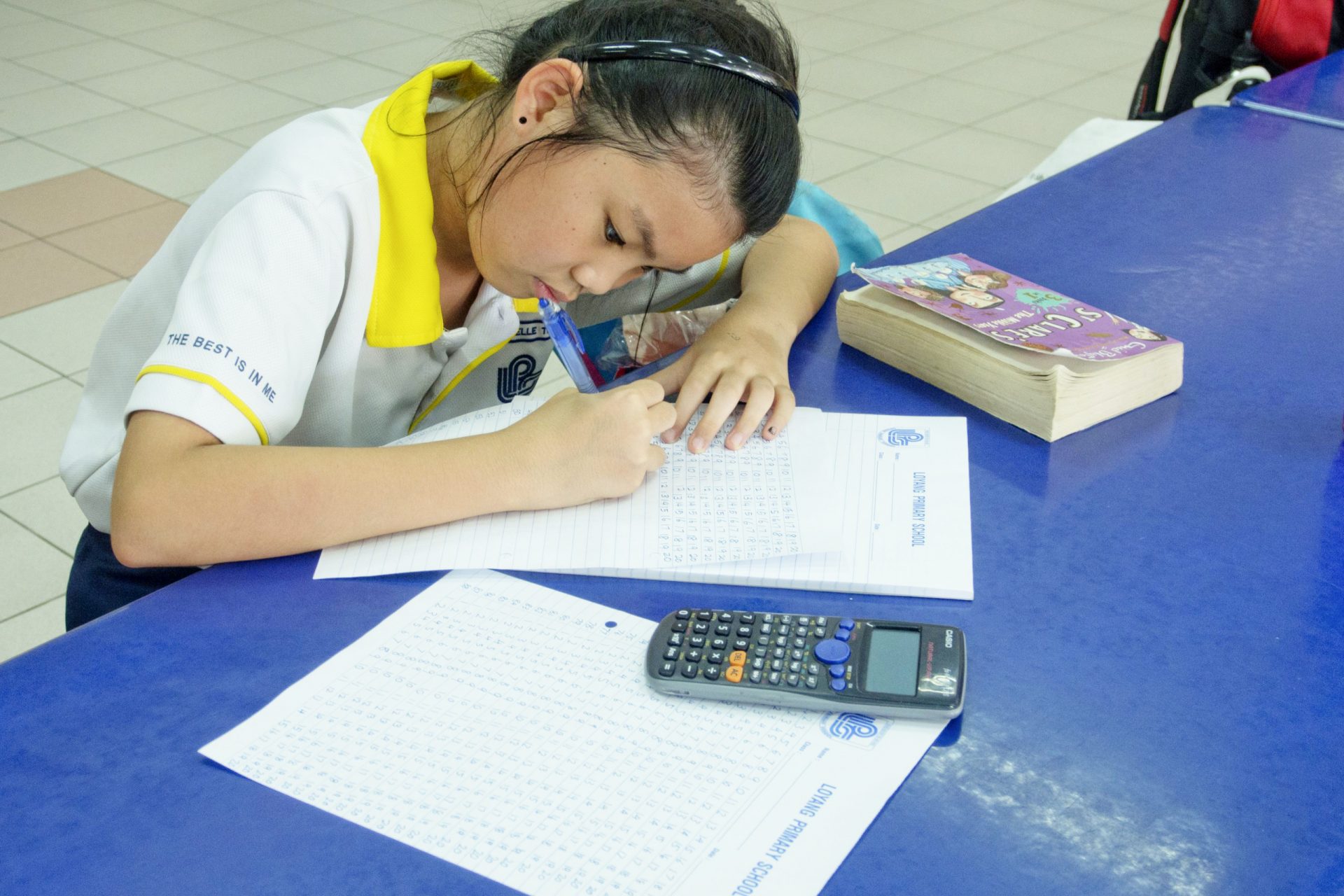

This is the case of Singapore; the country saw its results rise by 6 points in mathematics (standing at 575), and again placed first in all three tests: mathematics, reading and science. They are followed by Taiwan, Japan and Korea, which have also risen.

The Asian country has historically had very good results in mathematics. The gap between first and second place being 39 points in this last evaluation.

Singapore only has 5.4 million inhabitants and is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, but more is needed to explain its good results.

Singapore authorities believe that mathematics education is crucial to teaching thinking. From an early age, children learn to develop complex mathematical processes that involve reasoning, communication and modeling.

The distinctive approach to mathematics teaching in this country is known as the 'Singapore Method' or 'Mastery Approach'.

It was initially developed in the 1980s by the Singapore Ministry of Education for the country's public schools.

And in recent decades, it has been widely adopted and adapted for everyone.

Its approach is based on moving from memorization to a deeper understanding of what has been studied.

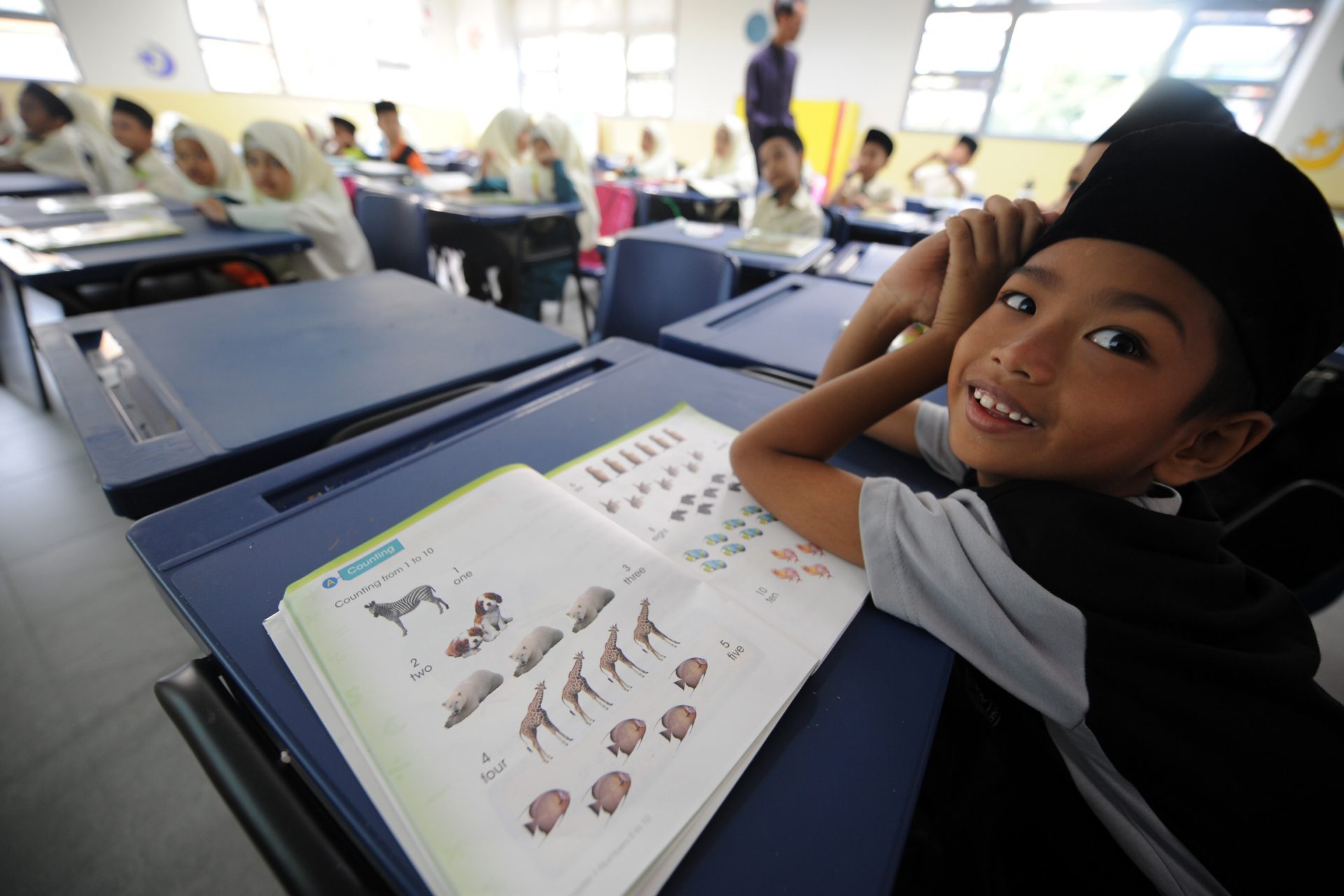

There are two basic ideas underlying the Singapore mathematics method: the 'CPA Approach' (Concrete, Pictorial, Abstract) and the 'Notion of Domain'.

The 'CPA Approach' is not unique to Singapore mathematics. It was developed by the American psychologist Jerome Bruner in the 1960s.

It is based on the fact that children, and adults, find mathematics difficult because it is abstract. This approach introduces abstract concepts in a tangible way and only then progresses to more complex topics.

"In Singapore mathematics, children always do something specific," Ariel Lindorff, a doctor and professor of Education at the University of Oxford, explained to the BBC.

"They can have addition cubes and put them together; they can draw; they can have pictures of flowers that they put together, or people or frogs or something that's easier to relate to and handle than just numbers," Dr. Lindorff says.

Until children understand the concrete and pictorial stages of the mathematical problem, they do not advance to an abstract stage of learning.

The 'CPA Approach' thus provides a way of understanding mathematics through representations. Something that does not depend on memorization.

Another pillar of the 'Singapore method' is the notion of 'mastery': all students in the class move forward together, with no one left behind.

As some understand faster than others, instead of advancing the entire group or stopping, some expand the information on the topic further, while others work on their understanding, until they are sure that everyone masters it.

The method is already used in other countries, such as the United States, Canada, Israel or the United Kingdom, but without equal results. Lindorff believes that "Singapore's success is related to its educational culture, context and history."

Teachers in Singapore have more promising career prospects. And children's attitude towards mathematics education is also different: it is not just solving questions for homework, it is solving problems for life.

More for you

Top Stories