Reality Check: Assessing the real risk of nuclear war today

The world is experiencing a highly dangerous period in its history. At least nine global superpowers are collectively armed with thousands of nuclear weapons, and many of them are increasingly at odds.

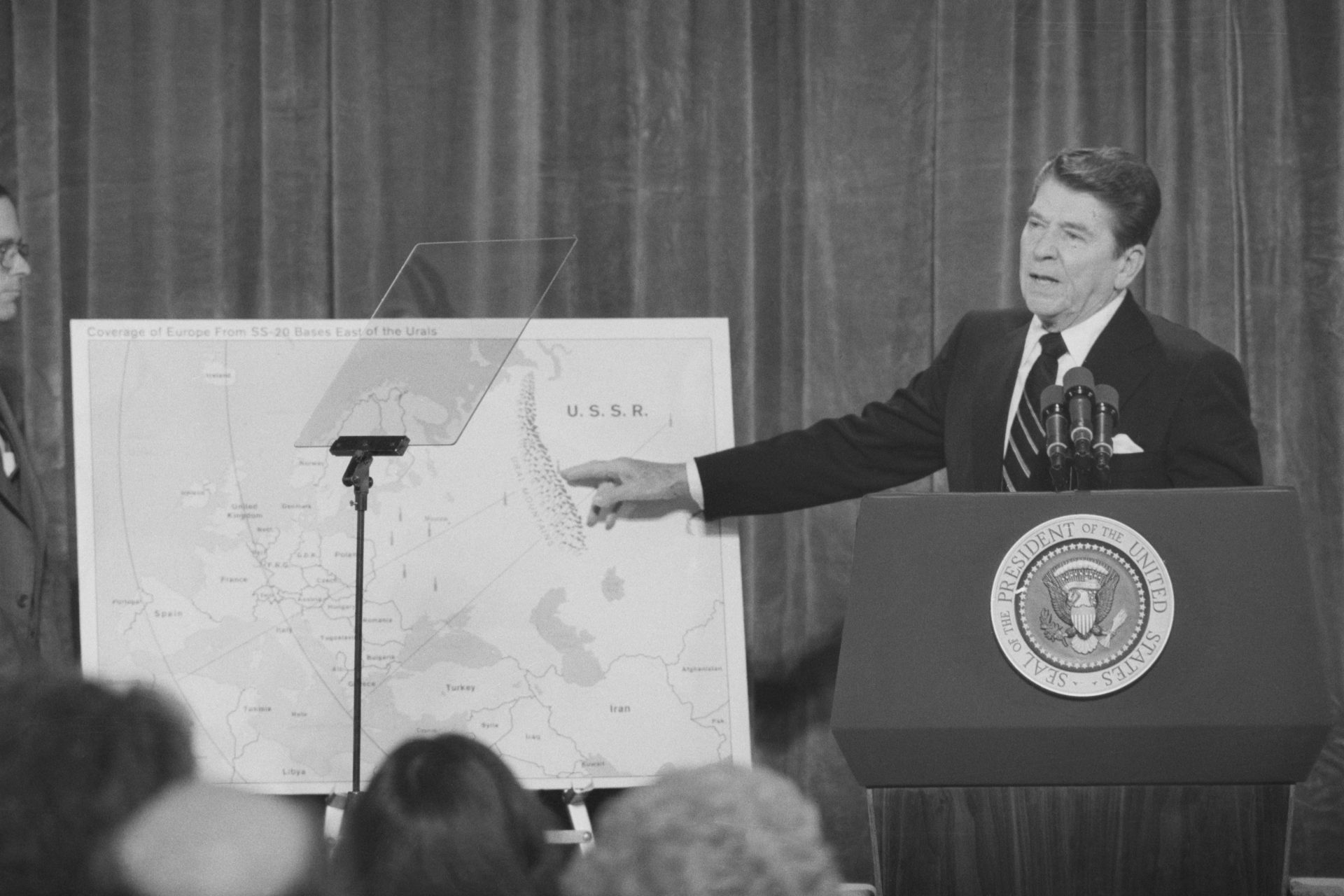

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has pitted the most powerful nuclear country in the world against the second-most powerful, along with at least four of its nuclear-armed allies, while China and North Korea are both emerging as new major nuclear threats.

North Korea could be the biggest wildcard threat on the nuclear chessboard since it has far less to lose than other nuclear-armed states and has shown a willingness to scoff at the global order that has prevented nuclear war for decades.

There are currently nine countries that possess a nuclear arsenal according to the Arms Control Association, and together they can field 12,100 nuclear warheads in the form of strategic and non-strategic tactical delivery systems.

Some of the world’s nuclear weapons are waiting to be dismantled but the number is far less than you might think. About 9,600 nuclear warheads are currently in military service yet that doesn’t reduce the odds of nuclear war.

Most of the world’s nuclear weapons are in the arsenals of the United States, which has a total of 5,044 nuclear warheads, and Russia, which has the largest arsenal of 5,580 warheads as of June 2024 according to the Arms Control Association.

The remaining nuclear warheads are owned by China (500), France (290), the United Kingdom (225), India (172), Pakistan (170), Israel (90), and North Korea (50). However, these are not the most likely nations to engage in nuclear war.

A fight between Russia and the United States is the most plausible scenario at present and it could be kicked off by the use of a tactical nuclear weapon in Ukraine by Russia, the probability of which was quite high at the start of the fighting and has only risen.

Former CIA Director and U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta remarked in an October 2022 Politico opinion piece that analysts had projected the probability a tactical nuclear weapon would be used by Russia rose from 1-5% to 20-25% just months into the war.

The New York Times even reported that the CIA warned Joe Biden the chances Russia would use a tactical nuclear weapon on Ukraine was sitting at 50% if Russian defensive lines collapsed and Ukraine looked as if it was going to take Crimea.

Whether or not Biden, or any other American President, would allow Moscow to use a nuclear weapon in Ukraine without consequences is unknown, but any one incident in 2024 may be the wrong question to ask according to some analysts.

Scenarios like a Chinese attempt to take Taiwan or an international incident that sees North Korea fire off its entire nuclear arsenal have too many variables. But it is quite probable that some major incident will be the catalyst for global nuclear catastrophe.

Famed Stanford professor Martin Hellman worked out that a person dying in their country due to nuclear war was 10% based on his analysis of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the events that led up to, and took place, during the incident according to a PhysOrg article on his work.

“The risk that each one of us dies as a result of failed deterrence is thousands of times greater than the risk you would bear if a nuclear power plant were built right next to your home,” Hellman explained in simple terms.

Hellman isn’t the only person who has tried to put a probability score on the likelihood of nuclear war. There have been several different individuals who have claimed nuclear war is inevitable given a long enough time.

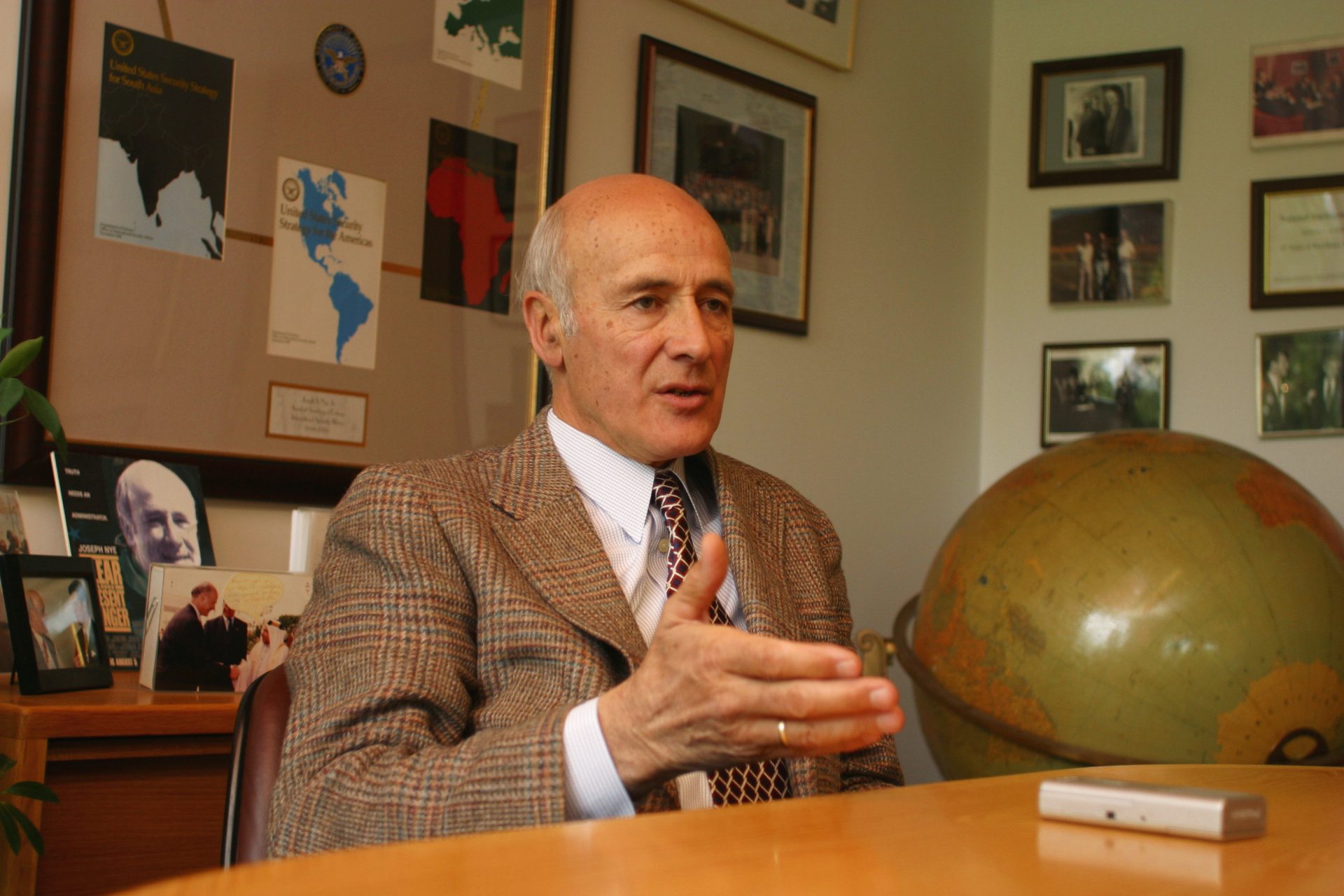

Former U.S. Assistant Secretary for Defense and International Security Affairs Joseph S. Nye noted in a widely published opinion piece in 2022 that in 1960 British scientist C.P. Snow declared nuclear war was “a mathematical certainty.”

Nye also quoted 1980s Nuclear Freeze campaigner Helen Caldicott who also once echoed Snow's warning, stating that the building up of nuclear weapons would “make nuclear war a mathematical certainty.” However, Nye doesn't believe in the inevitability of nuclear war.

“Those advocating the abolition of nuclear weapons often note that if you flip a coin once, the chance of getting heads is 50%; but if you flip it ten times, the chance of getting heads at least once rises to 99.9%,” Nye wrote.

“A 1% chance of nuclear war in the next 40 years becomes 99% after 8,000 years. Sooner or later, the odds will turn against us. Even if we cut the risks by half every year, we can never get to zero,” Nye added.

According to Nye, however, the coin flip metaphor wasn’t the right way to look at the possibility of an inevitable nuclear war, arguing instead that human interactions are more like loaded dice. We have the free will to make a choice.

“What happens on one flip can change the odds on the next flip. There was a lower probability of nuclear war in 1963, just after the Cuban Missile Crisis, precisely because there had been a higher probability in 1962,” Nye wrote.

“The simple form of the law of averages does not necessarily apply to complex human interactions. In principle, the right human choices can reduce probabilities,” Nye added, which is exactly what happened in 1983.

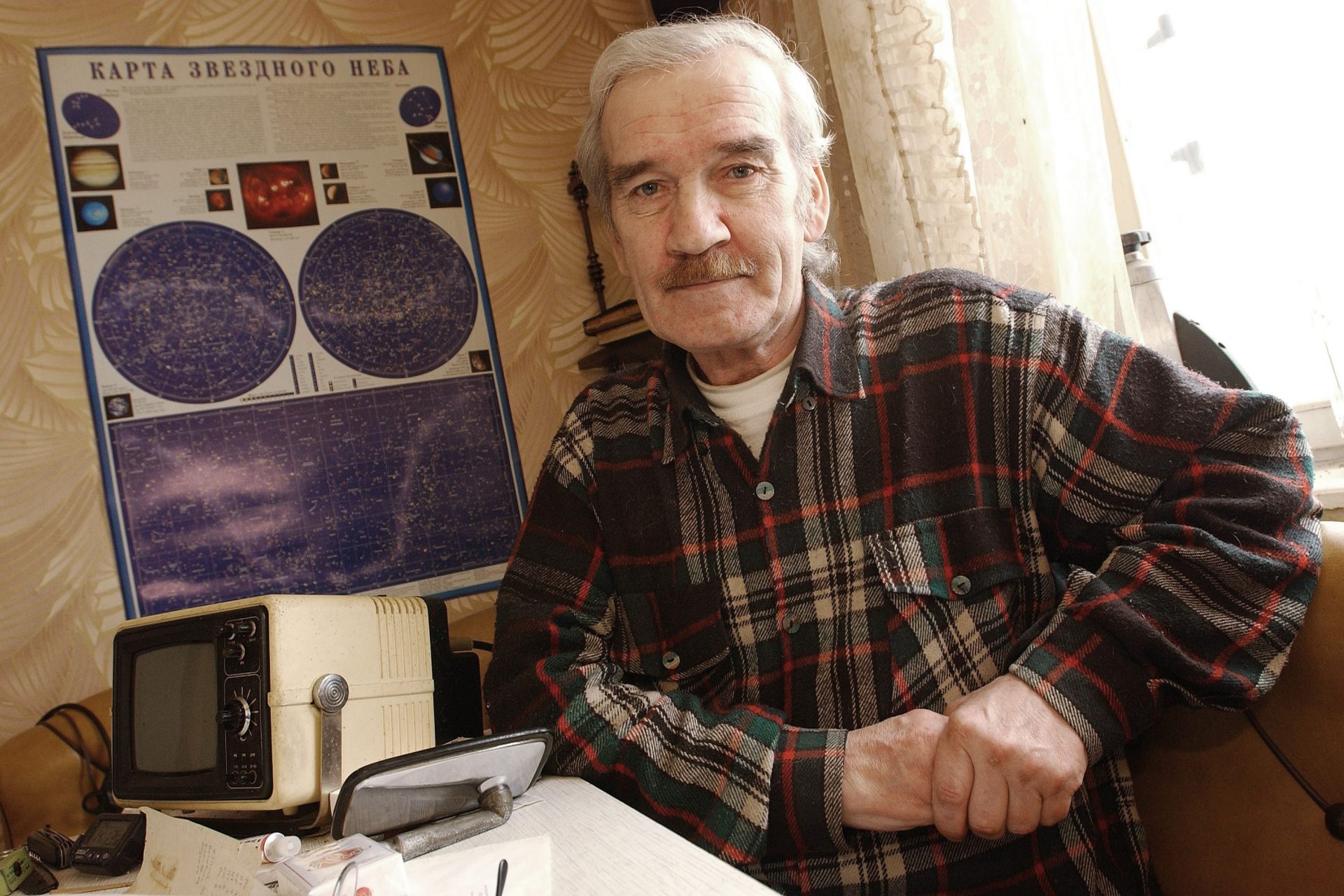

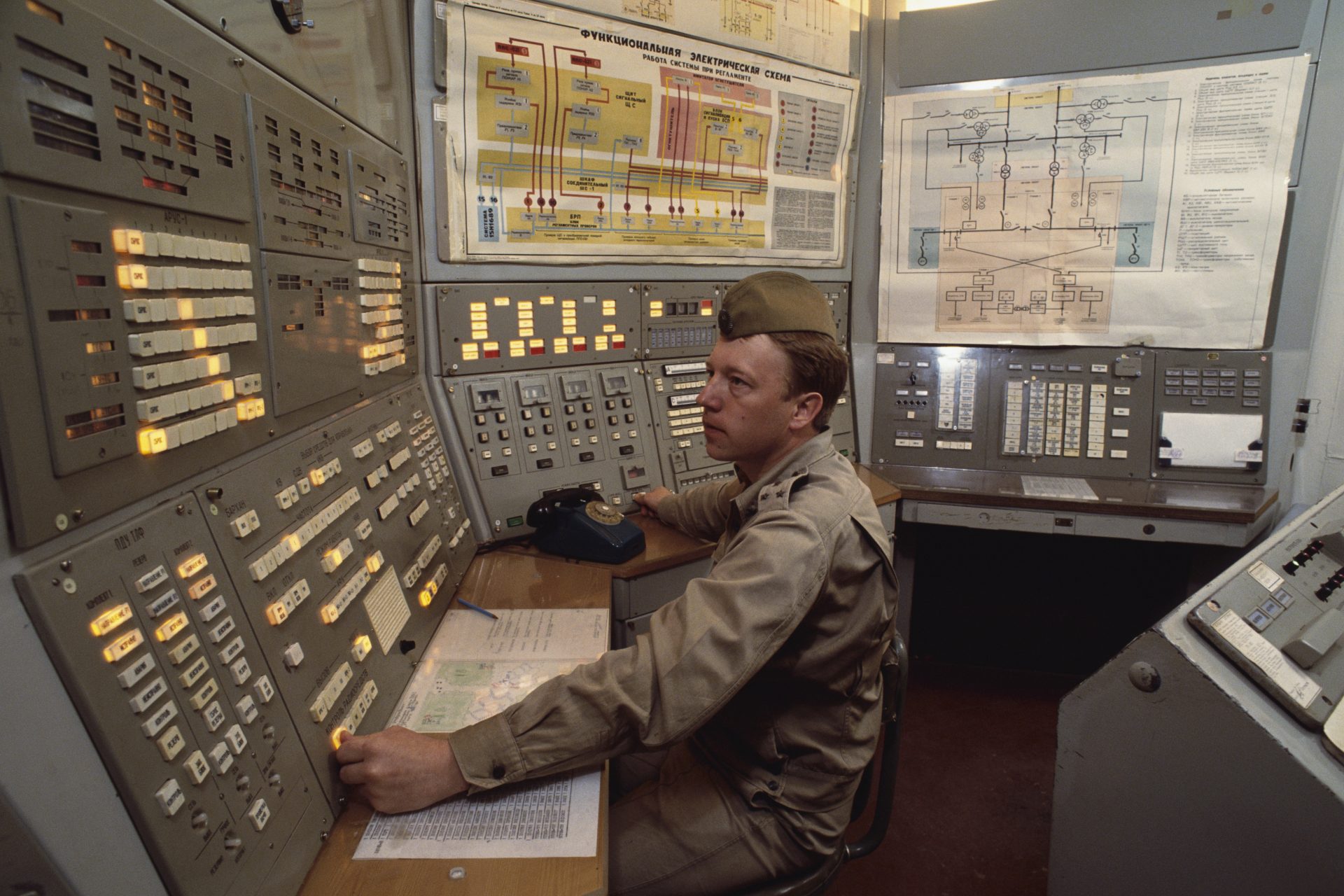

Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov saved the world from nuclear annihilation in 1983 when he disregarded computer readouts suggesting several missiles had been fired at the Soviet Union, a fact he didn’t report to his superiors according to BBC News.

The information was correct, and even though it was Petrov’s job to register incoming missiles and report them, he chose to dismiss the information which likely saved the world from a retaliatory strike and nuclear war. Human choice can and does make a difference, it would seem.

"I had all the data [to suggest there was an ongoing missile attack]. If I had sent my report up the chain of command, nobody would have said a word against it," Petrov told BBC News about the incident in 2013.

BBC News reported that Petrov never thought of himself as a hero. Instead, he told the British news outlet: "That was my job... But they were lucky it was me on shift that night."

More for you

Top Stories