Hostage diplomacy: Evan Gershkovich among three Americans released from Russia

After a months long negotiation, the Biden administration managed to secure the release of three American political hostages that had been held in Russia.

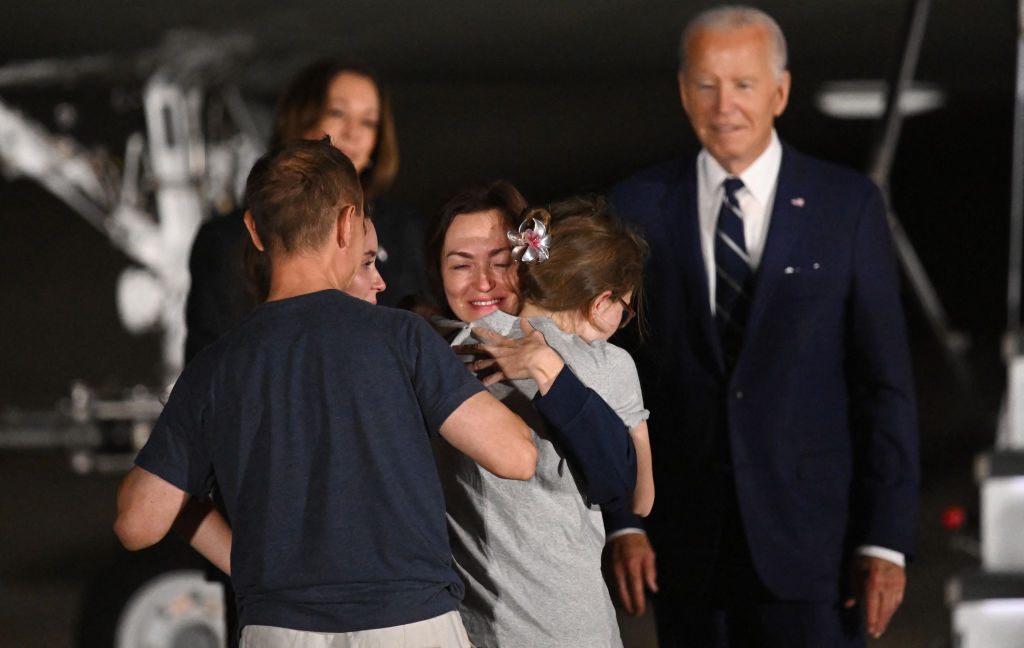

Photo: Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich hugging his mom.

Evan Gershkovich was detained in Russia in March 2023 and sentenced this July to 16 years in a maximum security prison after he was found guilty of espionage in a case that his employer, The Wall Street Journal, and the US government condemned as a sham.

Similarly, Paul Whelan, a former US Marine, jailed for alleged spying, was detained in 2018 and was held for 2,043 days, his family told The Washington Post.

Dual citizen (Russian-American) journalist Alsu Kurmasheva was detained in October 2023 and sentenced this July for “spreading false information about the Russian army”.

Photo: Kurmasheva with her husband and daughters back in the US.

This is the latest news in a practice so common it has its own name: hostage diplomacy.

Photo: WNBA athlete Brittney Griner when she was detained in Russia in 2022.

The detention of foreigners to influence the implementation of amenable political decisions, or prisoner swaps. Usually, the responsible government does not openly state its geopolitical ends, but it will imply that the captive’s fate is linked to broader hostilities or even to some specific demand.

The practice is often associated with authoritarian states like Russia, China, Iran, Venezuela, and North Korea: countries that have little international standing or foreign tourism to risk and may be desperate for leverage against American threats of regime change or war.

The United States is unusually vulnerable to hostage diplomacy for the simple reason that, as the world’s third-most populous country and largest economy, many of its citizens are within the borders of other nations, including hostile ones, at any given moment.

Image: Joey Csunyo/Unsplash

After being detained in a Russian airport in February 2022 for carrying a vape cartridge that allegedly contained cannabis oil, the Biden administration declared Griner to be wrongfully detained by Russia's government, believing Putin’s regime ordered Griner's arrest so it could use her as leverage.

At first, the Kremlin insisted the case wasn’t politically motivated. Spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said that he could only state the facts. "She was apprehended with forbidden compounds that contained narcotic substances," he said.

However, they later hinted at doing a prisoner swap that would get them Viktor Bout, a Russian arms dealer known as the “merchant of death,” serving a 25-year federal prison sentence for conspiring to sell weapons to people who said they planned to kill Americans.

Finally, in December of 2022, after 10 months in detention, Griner was released from one of Russia's most notorious penal colonies in exchange for Viktor Bout.

In the same way, the release of Gershkovich, Whelan and Kurmasheva was part of a 24-person prisoner swap, one of the largest since the end of the Cold War, among the U.S., Russia, Germany and three other Western countries, according to a CBS news report.

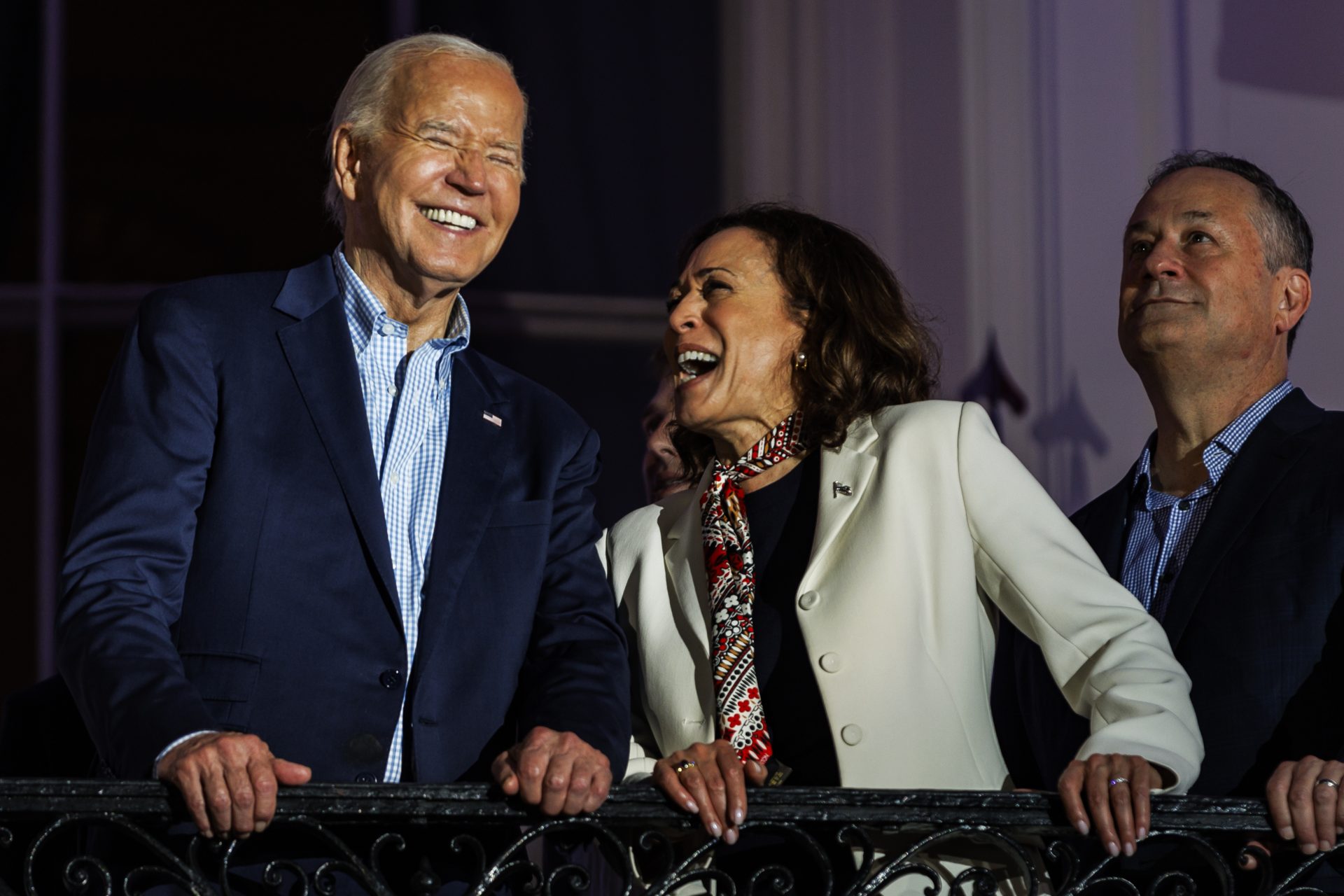

The release of the hostages was a win for the Biden administration who has been previously criticized by the families of detainees for not doing enough to get them home.

In 2022 Siamak Namazi, who was jailed in Iran since 2015, had an opinion piece published in The New York Times, where he said that the Biden administration's approach to rescuing Americans in distress in Iran had “failed spectacularly”, however, one year later, he was too released.

Iran is considered a leading offender, having arrested dozens of dual nationals, including imprisoning the Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian from 2014 to 2016 on espionage charges.

There was North Korea’s 2016 detention of Otto F. Warmbier, a college student visiting with a tourist group during a moment of high tension over North Korean missile launches. Warmbier was released 17 months later in a vegetative state and died days later.

Also in 2016, Turkey arrested a visiting pastor, Andrew Brunson, on espionage charges. The case was widely seen as intended to pressure Washington to extradite a Turkish dissident living in the United States. Though Washington refused to extradite the dissident, Brunson was released in 2018.

In 2017, as the Trump administration pursued efforts to overturn Venezuela’s government, the country arrested six American oil executives. There was little need to state explicitly that their fate depended on Washington’s actions.

Venezuela released one of those executives as Washington was discussing renewing oil imports from Venezuela to counteract rising prices.

However, time after time, Washington faces the same dilemma: If it engages with the hostage-taker’s demands, it also risks encouraging hostile powers worldwide to take more such hostages.

And then there is the question of how much attention to call to such cases. Playing them up can effectively increase the hostage’s value, making their quick return less likely. But engaging too quietly can risk conveying to foreign governments that hostage diplomacy goes unpunished.

But “Ignoring the problem, or obscuring it with diplomatic euphemisms and opacity, only helps the hostage-takers,” said Jason Rezaian, a journalist taken as a political hostage by Iran for two years. Now, however, it seems the Biden administration is doing much more to address the problem.

Never miss a story! Click here to follow The Daily Digest.

More for you

Top Stories